Story by Collin Morris, Assistant Sports Editor

“I remember sitting on my back porch one night with a 9mm handgun on my lap, and crying out for God to either show me a sign, or I would end my own life,” speechless Lyon County High School students heard last Friday as Zeke Pike recited for them his life story.

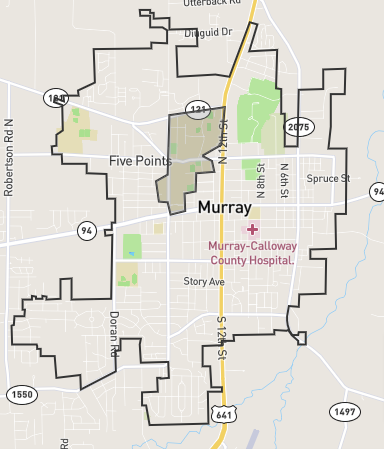

Just two years ago, in the late spring of 2015, Murray State welcomed a former four-star recruit and Auburn football signee onto its campus. The Racers were to be a third chance at meeting overwhelming expectations for Pike, a 23 year-old quarterback once rated Kentucky’s no. 1 overall recruit.

Rather than a revitalization of his football career, however, Murray, Kentucky ultimately became a near-death, life changing experience for Pike.

In 2012, after garnering national attention from elite schools such as Alabama, Florida, Michigan and Southern California, Pike signed with the defending national champion Tigers of Auburn University. Pike was to succeed then reigning Heisman Trophy winner and no. 1 overall NFL draft pick, Cam Newton.

Just a few months after his arrival on campus in Auburn, Alabama, a night of drinking with teammates led to Pike’s first of a series of arrests. Pike was taken to jail for public intoxication and later bailed out by an Auburn coach, who then escorted him back to his dorm room. A few hours later, Pike received a phone call from Auburn Head Coach Gene Chizik informing him he’d been released from the school’s football program.

Pike then returned home to Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, awaiting phone calls from any of the dozens of schools he had once been offered scholarships from. Weeks went by, but in August of 2012, Pike received a call from Charlie Strong, head coach of the University of Louisville Cardinals. It was there that Pike would be given a second chance, only to expand his previous addiction beyond alcohol and marijuana into prescription drugs. There, Pike met his girlfriend, Louisville cheerleader Dani Cogswell, who was also battling drug addiction.

A few months later, in early 2013, a Xanax-induced blackout found Pike face-to-face with a telephone pole he had driven himself and Cogswell into. Both emerged physically undamaged, but Pike’s football career was severely hindered after the police arrived on scene and charged Pike with a DUI.

Pike was then suspended from Louisville’s football team as well. From there, he and Cogswell departed for Gatlingburg, Tennessee, where Pike would be charged with yet another DUI only 14 days later. This time, Pike’s parents stepped in with a fearful ultimatum for their son.

Mark Pike, a 12-year NFL veteran with four Super Bowl appearances for the Buffalo Bills, along with his wife, Sharon, sternly warned Pike.

“My parents are sitting in my dorm room and they look at me, and they say, ‘either you go to treatment, or we’re done with you and you can figure this out on your own,’” Pike said. “That day I got on a plane, flew out to California and I enrolled in a treatment plan.”

Pike enrolled at Sober College and achieved five consecutive months of sobriety, allowing him a 10 day visit home with his parents and girlfriend. Pike said he saw that week and a half as an opportunity to prove to his family his commitment to a new direction, as well as a chance to check on Cogswell, who had been left to cope with her addiction alone.

Cogswell had spent time in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, throughout the week, but on the eighth day, she returned home to Louisville, Kentucky, with the intention of picking up clothes to stay with Pike for the remainder of his visit.

That night, Cogswell fatally overdosed on heroin.

“Five months of sobriety and I just lost my best friend and my girlfriend, so the only thing I know to do is to run right back to drugs; now I was a full blown junkie,” Pike said.

Months later, Pike received a phone call and scholarship offer from Murray State football Head Coach Chris Hatcher. Only four months after that, Pike was arrested for his fourth DUI and released from the third football program of his career.

Pike then lost all communication with his parents and resorted to drug dealing to pay his bills and fuel his own overpowering drug addiction.

“I remember sitting on my back porch one night with a 9mm handgun on my lap, and crying out for God to either show me a sign, or I would end my own life,” Pike said. “And I sit there for a few minutes, I take some more pills, and I decide this is it. So I put the clip in my 9mm, take the safety off, put the gun to my head and right before I pull the trigger, my phone rings.”

Pike said the call was from just another addict looking for a fix, but it stopped him long enough to realize he couldn’t allow his mother find him dead on his front porch.

“So, I decide I’m going to get in my truck, drive to the woods and end it once and for all,” Pike said. “Hopefully I’m never found, and if I am then my body is already decayed and I’m not really recognizable.”

On his way away from the city limits, and in a haze, Pike was pulled over and arrested for his final time; charged with four felonies and facing 14 years in prison, Pike was able to serve a mere eight months.

Pike told this story with remorseful eyes as he paced the gym floor of Lyon County High School; with 265 students looking on, he sought to warn them of the dangers caused by experimentation with drugs and alcohol.

“I wish somebody would’ve told me when I was in high school that 90 percent of addiction starts in your teenage years,” Pike said. “I wish someone would’ve came and stood before me like I’m doing today.”

Lyon County joins over 30 other schools across the southeast that Pike has visited as part of his tour to promote drug awareness. Pike says his traveling comes as part of his new initiative, Number 8 Ministries.

“Number 8 stands for new beginnings, which has a lot of biblical meaning behind it, and we’re trying to give people a new opportunity to create a new beginning for their life and give people hope,” Pike said. “Basically, our ministry is to travel and speak to share my story but we’ve also got a guy who does a lot of clinical addiction treatment and counselling, so we’re trying to create some outlets in other regions.

Pike said his ministry looks to support all individuals facing addiction or other mental health issues, but his other upcoming project – Replay — will be athlete-oriented with focus on athletes who have been suspended or kicked off of their teams for drug and alcohol-related incidents.

“We’re trying to really give athletes the opportunity to get clean and get their lives back in order, and not have to waste five years of eligibility and then open your eyes and addiction has taken over your life like what happened in my situation,” Pike said.

Pike also said he hopes to meet with the NCAA in the coming months to collaborate in their efforts to fight these diseases.

“If you blow a knee out, you don’t lose a year of eligibility for that, you get a medical redshirt year,” Pike said. “What’s the difference between that and someone who’s trying to better their life, end their addiction and not lose their opportunity to play sports and make their dreams come true?”

While Pike certainly believes there’s more to be done for athletes facing adversity, he said doesn’t fault the programs he previously attended for his own personal struggles, including Murray State.

“Murray State was really good, Mitch Stewart is a great guy and coach and I still have a good relationship with a lot of people there” Pike said. “There just kind of became a point where if I’m not doing what I need to do off the football field, there’s no tolerance for that anywhere. There could be more for every university to do to make sure when kids are suspended that they’re bettering themselves and getting the help they need. But the people at Murray State will always have a special place in my heart.”

Pike said the issues of mental health and addiction are not only prominent in sports, but in every aspect of life.

“This disease of addiction affects everyone,” Pike said. “As a young person who has to go home to that, and they have to go home and see their mom and dad or brother and sister struggling, those kids need help and support and they need an outlet they can talk to. These kids don’t want to admit that when they go home it’s miserable, and they need to know people care about them. We, as a society and as a country, need to take under consideration, are guidance counselors class schedulers, or are they people who are in schools to help students out?”