When I was a kid, I once told a lie. This was a world-class whopper.

Lies were not very good strategies for bonding in my family; although our mother was the soul of charity and forgiveness, it was her custom to refer the heavy lifting in the discipline department to a specialist – to The Old Man. You might be able to relate. In any event, I had concocted a tale which, under different circumstances, might have led to a Pulitzer in fiction or, at the very least, a job as a speechwriter for a Congressman.

The details are unimportant, but you can trust me when I tell you that the “facts” and the manner of my telling them were accepted hook, line and sinker by Mom, who shall be known from now on as, “Mom.”

However, as Bill Clinton discovered, a secret known by more than one person is simply a scandal waiting for its moment. Hence, when my younger brother opened his mouth on the subject of a damaged bicycle and torn and muddy pants, the truth was revealed.

I was sentenced to “wait in my room” for what seemed like the entirety of former President Eisenhower’s second term. When The Old Man entered, he was not in a pleasant mood.

He proved it by launching into an examination of my morals by asking me, “Why did you lie to your mother?”

This is the kind of question no kid can answer. The correct response, I now see, would have been: “Why, to avoid this very moment of unpleasantness, of course. Are you nuts?”

This clever response would not have been wise, although it would have been honest. Instead, I did the best I could under the circumstances, which was to resort to the good old childhood standby: “I dunno.”

I don’t recall what the penalty for lying was in this case, but it put me off the practice entirely until I got married.

The real “takeaway” for me, however, was the realization that adults could ask what seem to be really stupid questions.

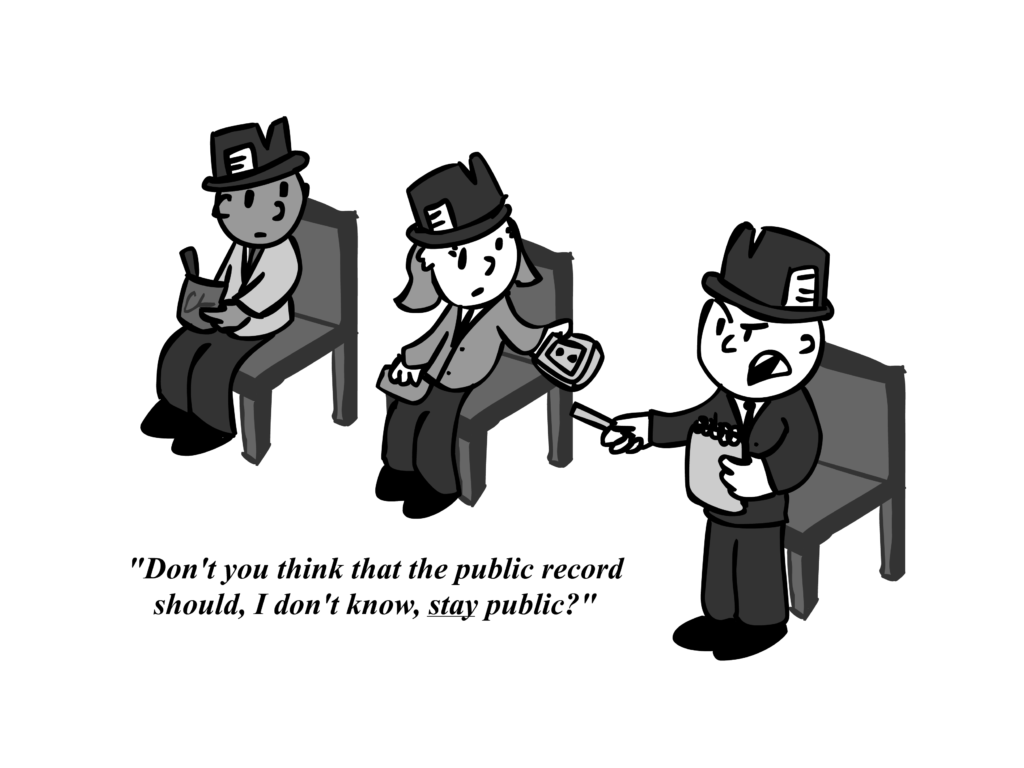

A few weeks ago in this space I suggested that students, despite their current devotion to learning and the development of the mind, sometimes ask fairly stupid questions like, “Uh, did we do anything in class today?”

This suggests to the professor that his usual in-class practice is to read aloud from “Uncle Wiggley Meets the Alligator,” or to play checkers with the brainy kid in the front row. Not a good conversational strategy.

Turn about is fair play, however, and it’s only fair to point out that professors can ask some goofy ones, too. See if any of these would make your personal Top Ten.

- “So, should we postpone the exam until after Spring Break, or would you rather take it the Friday before?”

- “Now, does that answer your question?”

- “Why don’t you get together with your group outside of class? Can’t you find an evening when everyone is free?”

- “Don’t you remember that from your reading of the syllabus?”

- “I know we’re a few minutes over time, but would it be OK if I just finish out this equation?”

- “Would you prefer the one-page take-home test or an open-book essay exam in class?”

- “I know it’s early on a Friday morning, but where is everybody? Does something happen on Thursday night around here?”“

- “Do you mind if we wrap things up a bit early this evening?”

I suppose the point is this: all of us should probably think for just a moment before putting questions to unsuspecting people. Sometimes, the answer is known, and we use the question as a cruel way to compel an admission of failure; sometimes we merely forget to whom we are speaking. Questions, like a ringing telephone, demand to be answered.

Perhaps we should use such powerful tools with much greater care than most of us professors usually exhibit, Y’know?

Well, that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it like secrecy to a presidential search.