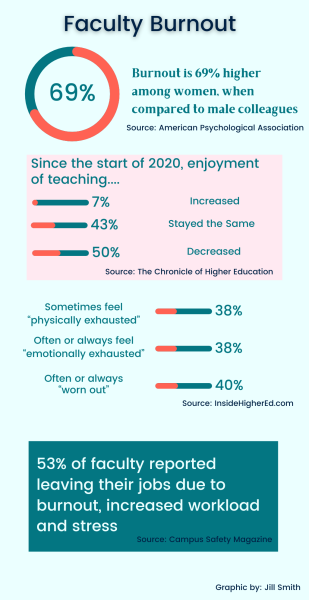

The impact of chronic workplace stress on faculty well-being was a concern for academic leaders pre-pandemic. Still, faculty burnout has reached a tipping point over the past few years.

A study from the Healthy Minds Network reports that 64% of faculty surveyed feel burned out or exhausted. At Murray State, faculty feel the effects of burnout daily.

Claire Fuller, dean of the Jesse D. Jones College of Science, Technology and Engineering, said her experience with burnout was impacted by COVID.

“I was fairly new to the dean’s job at that time and had a number of initiatives I was interested in pursuing as dean,” Fuller said. “Those got put on the back-burner as we pivoted to working to provide an excellent education in the face of COVID. Things didn’t get back to normal for a long time – some would say they still aren’t back (to normal) – and in that time period, I became burned out.”

Antje Gamble, associate professor of art and design, said her burnout has impacted her teaching.

“Teaching is separate in the sense that the energy to really want to update classes and make new experiences for students,” Gamble said. “I think the above and beyond has gone away. I’m still trying to do those things, but I just have less energy and really, frankly, time to do it. In part because I know I need to rest, but we’re always being asked to do more.”

Danish researchers recently released a study highlighting the gender gap in academia- specifically service work.

After a series of interviews with male and female faculty, researchers determined that men are more likely to avoid service work (committees, leadership and coordinator roles).

“The interviews with men associate professors show a very different relationship to internal service than the one reviewed above,” according to the study. “In fact, more than half of them practice evasive relational work, meaning that they actively try to avoid these kinds of tasks”

Andy Black, associate professor of English, said one issue he and other faculty members have is questioning the job and its importance.

“I think one of the biggest issues that I – and any professor has – is ‘Why does what I do matter?’” Black said. “I have a lot of different answers for this question – that the work in my classroom is vital – but some days I come home feeling discouraged and unproductive. But I’m glad to say that within a few days, after a good class filled with productive conversations by engaged students, I’m able to move beyond this. But it’s tough sometimes, and the pandemic only exacerbated that.”

Gamble said she does not believe the University is taking the well-being of its employees seriously. Gamble remembers a meeting between the Gender Equity Caucus and key administrators.

“We had lots of immediate concerns because people had their kids at home, they were taking care of their parents or siblings,” Gamble said. “It was a lot. Then we were also signaling long-term concerns like burnout, and I don’t think those concerns were taken seriously at the time. They don’t seem to be taken seriously now.”

As dean, Fuller said she takes burnout seriously among her faculty.

“We do take burnout seriously and know faculty struggle with it, especially during/since COVID,” Fuller said. “My hope is that those struggles have gotten better for most people. We try to help at both the collegiate and departmental level by being flexible, providing information about resources to help with mental health issues, etc. We have tried to increase social and collegial interactions within departments and across the college.”

Black said hearing his impact on students, even former students, is enough to remind him of the importance of his work.

“A few weeks ago, I heard from a student from a few years back that I had made a difference in her life,” he said. “That I had helped her. That was enough to remind me that I could do productive work even when I didn’t realize I was doing it. Every time I feel burned out, I try to remember that it’s the students that matter.”