For my inaugural artist spotlight, I have forgone the usual formula of highlighting an up-and-coming musician. Instead, I have chosen an artist whose impact on American culture cannot be understated, though he isn’t a household name. That artist is Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, mentee of Woody Guthrie and mentor to Bob Dylan, who solidified the idea of the traveling folk singer in the American consciousness.

A tribute concert to him was held in San Francisco last week with performances from Joan Baez, the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir, Steve Earle, Jackson Browne, Sarah Lee Guthrie (granddaughter of Woody Guthrie) and many others. It concluded with a performance by Elliott himself.

I wish I could say I dropped everything and flew across the country to attend what I imagine was a fantastic event. Alas, a few stray YouTube clips will have to suffice. However, news of the event did lead me to think about the time I was lucky enough to see him perform, which I will chronicle later in this column, and how incredible it is that such a legendary figure is not only still with us at 92 years old, but is still performing.

Ramblin’ Jack was born Elliott Charles Adnopoz, the son of a prominent Jewish doctor in Brooklyn, New York. The path to his future troubadour persona couldn’t be more romantic. At the age of 14, he fled his unhappy home life and the expectation that he would go to medical school to join a rodeo, where he learned to play guitar from a cowboy.

An important distinction about Elliott is that, unlike many folk icons, he is not famous for writing his own songs. He’s written two in his entire career, “912 Greens” and “Cup of Coffee,” the latter of which Johnny Cash covered on a 1966 album. I’ve heard Elliott joke that he may be the only artist that had half of his songs recorded by Johnny Cash. Instead, Elliott’s signature is his interpretation of others’ songs and his long, delightfully meandering stories. As the saying goes, they don’t call him Ramblin’ Jack because he travels a lot.

His most famous interpretations are likely of songs by Woody Guthrie, who Elliott befriended, traveled with and even lived with for a time. For many, Elliott’s versions of songs like “This Land is Your Land,” “1913 Massacre” and “Philadelphia Lawyer” are as essential as Guthrie’s recordings. Guthrie allegedly stated that Elliott “sounds more like me than I do.” Elliott similarly made his mark on countless folk standards like “Wabash Cannonball,” “Railroad Bill” and “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”

Beyond the influence of his own work in folk music, his effect on Bob Dylan is also significant. While Dylan’s idolization of Woody Guthrie is well known, his early folk persona – nasally delivery included – was more directly shaped by Elliott. Being an early influence on the man who would become this century’s most influential songwriter is certainly a feather in the cap of Elliott’s musical career.

Like any proper folk hero, Elliott has been immortalized in song by some of the great songwriters of the 20th century. This includes Kris Kristofferson’s “Ramblin’ Jack” and Guy Clark’s “Ramblin’ Jack and Mahan” and “Cold Dog Soup.”

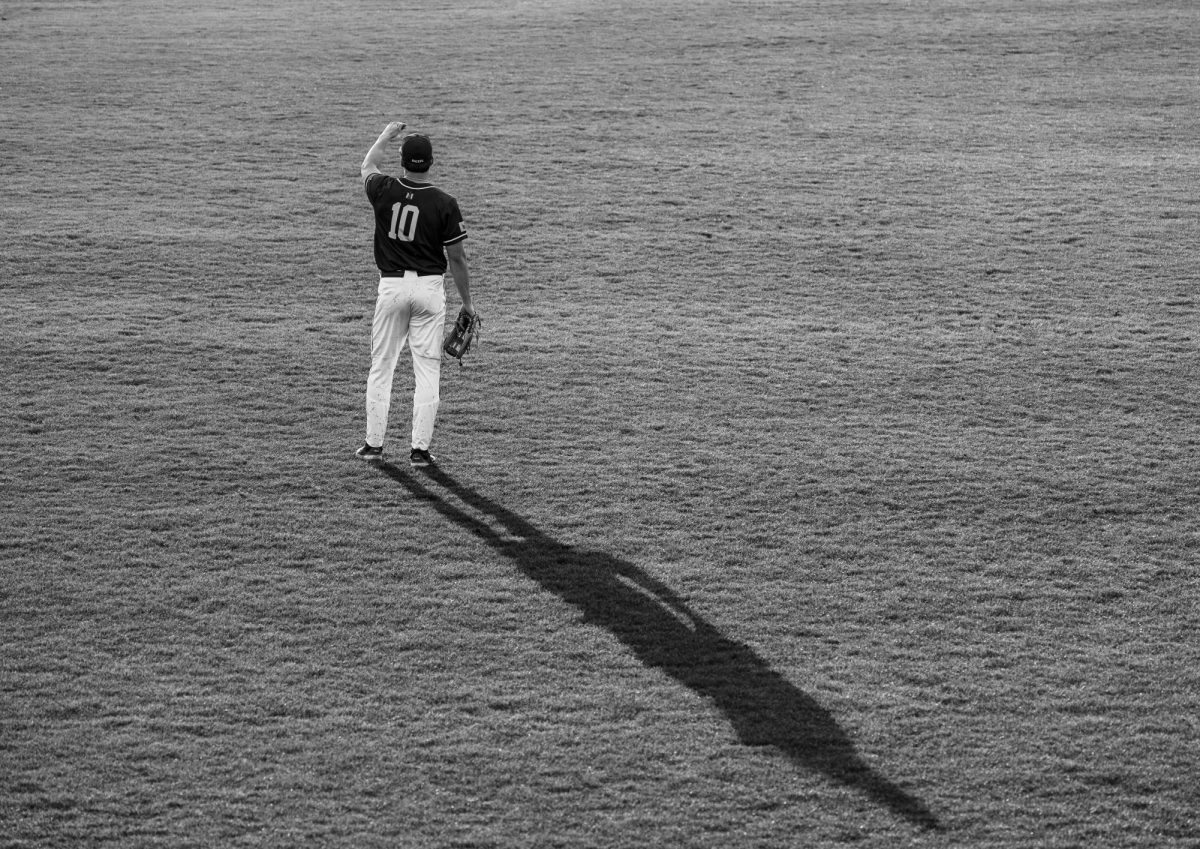

As for my own experience seeing Ramblin’ Jack Elliott perform, I saw him open for Todd Snider at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville in 2022. The chance to see Snider, an extremely personal artist to me, along with a living legend in a venue with deep historical significance was one I couldn’t pass up.

It didn’t disappoint. Elliott did a lovely half hour of singing and storytelling and returned to the stage after Snider’s set to sing “Muleskinner Blues” with him. Snider’s admiration for Elliott came through in his own performance and elevated the show even further.

Through an odd series of events and unbelievable luck, I also ended up in the front row of a secret show Snider held for superfans at a smaller venue the next morning. Elliott made a surprise appearance at this show, and I saw the legend perform again from a few feet away.

I was the first person Snider saw when he came out to greet fans after the secret morning show. I suppose he was either charmed by or took pity on an awkward 20-year-old with songwriting ambitions trying to play it cool in front of one of his heroes. After a short conversation, Snider graciously told me to stick around until he was done shaking hands, taking pictures and signing autographs so he could take me backstage and talk to me a minute.

Two days before, I had never seen either of these artists live. Now, I was standing in a small green room with them and a few of their friends. Since Elliott wasn’t involved in inviting me back, I was sure not to try to inundate him with questions. I simply shook his hand, thanked him for doing the show and got him and Snider to sign my poster, which is now a prized possession of mine.

For days after I shook Elliott’s hand, all I could think about was all of the artists who almost certainly shook the same hand: authors like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, who were formative in my literary taste, and so many of my favorite songwriters and musicians that I could double the length of this column if I named them all.

More so than any visits to museums or historical landmarks, I was overcome with the power of history in that moment. And, of course, I spent the next week writing a song about it.

The perfect introduction to Elliott’s work is the compilation album “Best of the Vanguard Years.” Beyond that, make sure to listen to the two songs he’s written, “912 Greens” and “Cup of Coffee.” If you’d like to dive deeper into his catalog, “Ramblin’ Jack Elliott Sings Woody Guthrie,” “Young Brigham,” “Kerouac’s Last Dream” and “Country Style/Live” are essential.