Cady Stribling

Features Editor

cstribling1@murraystate.edu

Iris Snapp

Contributing Writer

isnapp@murraystate.edu

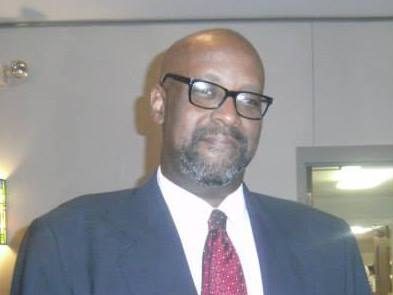

Alumnus and professor of history Brian Clardy recently had his article “Blood at the Root: A Historiographical Commentary on Lynching in America” published in “The Journal of the Jackson Purchase Historical Society.” With a history of its own, the scholarly article has been in the making for over 20 years with influences originating from Clardy’s time as a graduate student.

At Southern Illinois University, Clardy said he was a graduate assistant for Julius Thompson, a professor who was doing research on the age of lynching in Mississippi. Clardy often gathered sources for Thompson, but even as a graduate student, Clardy said he was uncomfortable dealing with the topic of lynching as it was very painful for him.

“I wanted to do something on lynching as a historian,” Clardy said. “I am a diplomatic historian by training, that’s true, but I’m also an African American male and I’m also a southerner. For me to ignore that history and not to at least help to contribute to the public’s understanding of that, I would have felt like a coward honestly.”

Growing up, Clardy had heard of various lynchings or stories of racial violence in the past from areas close to him. Particularly, he had heard of a lynching that happened in the 1930s in a town fairly close by in Tennessee. Clardy had seen photographs of the victims that were ritualistically taken at the lynchings, and Clardy said these photographs—and seeing the mobs standing around the victims as if they’d done something great—were very disturbing.

But mustering the energy to really focus on lynchings as a historical act, Clardy said, happened a few years ago after learning about the lynching museum in Montgomery, Alabama. Clardy and his church visited the museum around the time that Clardy’s pastor asked him for a favor.

“He texted me one day and asked me if I would lead a discussion over James Collins’ classic work of ‘The Cross and the Lynching Tree,’” Clardy said. “Oh, I’m not going to turn my priest down, so I told him I would and I got the book.”

Around the same time, Clardy left for the lynching museum.

“It was a very gripping monument,” Clardy said. “That and the Legacy Museum. Going on that trip for the first time gave me a whole lot of voice. It gave me my voice basically to really talk about and wrestle with the question of lynching.”

Clardy soon returned to the museums with Murray State students during Spring Break in 2019. He said the museums still had the power to shock him and get him thinking about the legacy of racial violence.

Clardy chose to deal with lynching through a historical lens by focusing on case studies in western Kentucky that had happened. He said he wanted to give the Jackson Purchase readers a digest of why and how lynchings happened, how they impacted western Kentucky and what the practical implications are for racial violence today.

Clardy chose his title “Blood at the Root” from the Billie Holiday song “Strange Fruit,” which he used as a guide as he worked through the article.

He began his research by looking at two local lynchings: the 1908 racially-motivated murder of the Walker family in Hickman, Kentucky, and the 1931 murder of George Smith in Union City, Tennessee. Clardy heard about these murders growing up.

“The first thing I did was look at the literature,” Clardy said. “I looked at the historical literature on lynching and looked at the popular works on it. There was a work done in the 1980s by a man who actually survived an attempted lynching named James Cameron. He wrote about his particular experiences in Marion, Indiana, in the 1930s called ‘Time of Terror.’”

Clardy examined works from well-known and unknown authors, newspaper accounts and reports from the Equal Justice Initiative and the NAACP. Clardy said he even looked at various maps of where different lynchings happened, trying to find something that connected them.

“I did find that there were some common threads among them,” Clardy said. “This view was that the person who was lynched had violated some social norm, that they were considered uppity, that they had committed an imagined crime or maybe even a real crime and were not given the benefit of due process.”

The cases made Clardy feel more inclined to write a commentary on the history of lynching when he realized the people who had been attacked did not get their due process.

These literatures and primary sources gave Clardy the idea on how best to construct the narrative he wanted to tell. Clardy took the research and information he found from the past and compared it to the racial implications it has today.

“As it turned out, I did all of this long before George Floyd,” Clardy said. “It was so interesting that George Floyd’s murder happened as I was in the process of revising this thing, and the parallels are very, very striking. What happened with Breonna Taylor and what happened with Ahmuad Arbery, all of this is happening as I’m finishing up the project. You talk about serendipity.”

A struggle that went back over a quarter of a century, Clardy said he was glad he carried out the project for public reading and is glad that it’s a part of his scholarship record.

As an addition to his research, Clardy gave presentations at the Calloway County Public Library and the history department research forum.

Clardy said he does not enjoy studying racism, but it is a history that we need to understand.

“The reality is that it does exist, so to be able to study and examine how and why there has always been this racialized element within American society [is important],” Clardy said. “We’re still going through that, but if there’s going to be any hope for America to become a truly multiracial and inclusive society, that is a history we need to wrestle with.”