Keaton Faughn

Contributing Writer

kfaughn1@murraystate.edu

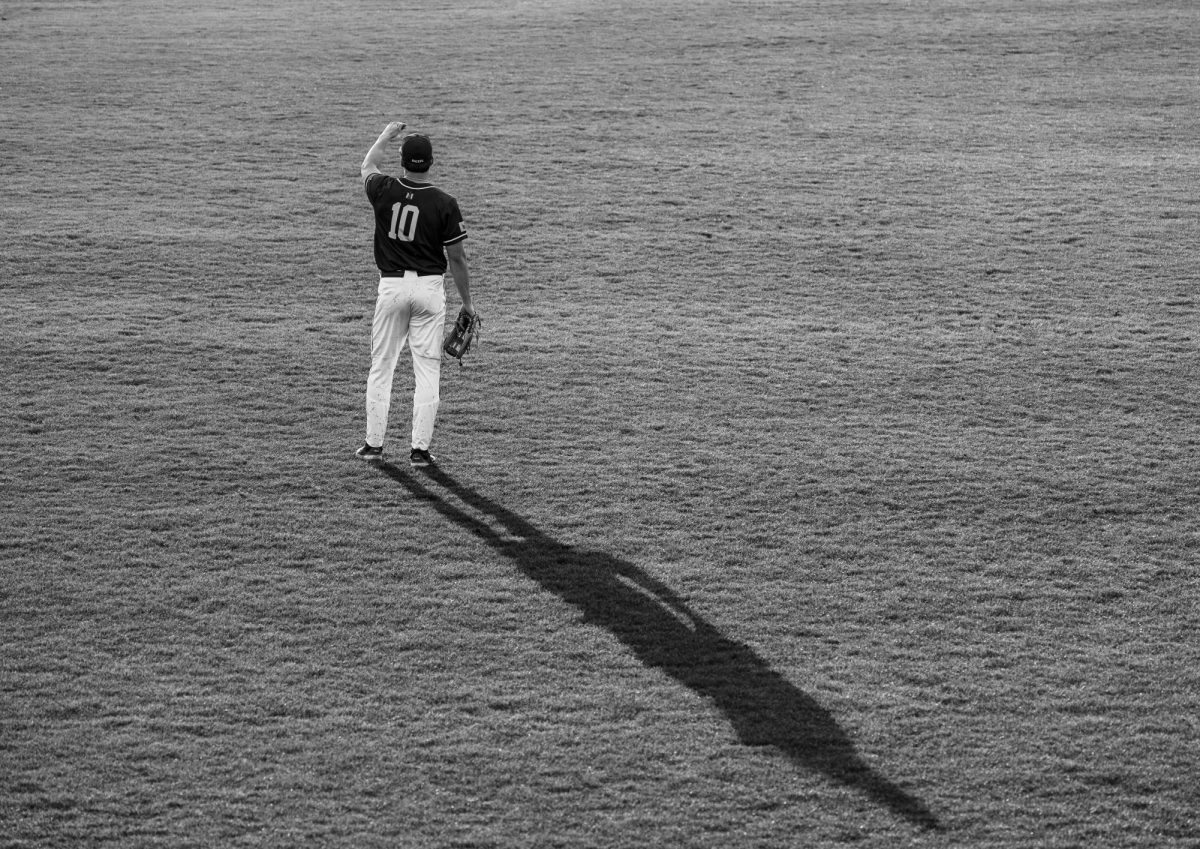

On Saturday, Sept. 7, the University of Georgia football team took the Murray State Racers to a 63-17 defeat in a money game, a common practice that is as old as collegiate athletics itself.

Larger schools have always played much smaller programs during their regular seasons. These “money games,” also known as “guarantee games,” date back to 1916. The infamous 222-0 beatdown by John Heisman-led Georgia Tech University of Cumberland College is one of the first in a long history of these money games.

The payout for these games help smaller programs or mid-major schools gain money to boost their respective athletic programs. The large powerhouse programs pack the house for these games, keeping fans happy with a usual blowout win.

When the Racers traveled to Athens, Georgia, for their second game of the year, the Bulldogs took the opportunity to rename their field in honor of their legendary coach Vince Dooly, and it is no coincidence that they chose a guarantee game to honor Dooly.

While Murray State has played some larger schools in the NCAA recently, they didn’t take those challenges without leaving with some financial gifts from their opponents. Racer Athletics was paid $550,000 for the team’s trip to the deep south.

Murray State Athletic Director Kevin Saal said the funds from money games like these go to support the global athletics department budget and are used as strategic investments in the growth and development of our football program.

This is where the root of the money games lie—where participants of a struggling athletic program can be paid to play a team that will almost certainly dominate them.

In only the first several weeks of college football this season we have already seen a few, one being the Georgia State University vs. University of Tennessee game. The Volunteers lost a game that cost them $950,000.

However, this is a rare example among money games, with most of them ending up in a loss for the smaller program and even a pileup of injuries that can affect the rest of their season.

Murray State’s game was no exception to this, but it isn’t the first money game the Racers have had in recent memory.

Saal said these games have been an important part of the Racers’ scheduling philosophy for many years.

Past schedules support this philosophy. In 2003, the Racers played at the University of Kentucky, which Saal said was a guarantee game.

“Same with UConn in 2004, Mississippi State in 2005, Missouri in 2006, Louisville in 2007, Indiana & WKU in 2008, NC State in 2009, Kent State in 2010, Louisville in 2011, Florida State in 2012,” Saal said. “Missouri & Bowling Green in 2013, Louisville and Western Michigan in 2014, Northern Illinois & Western Michigan in 2015, Illinois in 2016, Louisville in 2017, Kentucky in 2018, etc.”

The Racers took home $450,000 for their week one 69-3 defeat at the hands of the Seminoles in 2012.

Murray State is not only a benefactor of these money games, but Saal said they have paid schools to come and play before and will continue to strategically do more in the future.

“Typically, a senior administrator [or the AD] and Head Coach [or Director of Operations] are involved in developing the schedule,” Saal said. “Initial contact is mutually initiated between the payee and the payer.”

These games are a common practice among college football programs, with FBS teams paying to host FCS, teams as well as other FBS teams. The costs of these matchups vary, but the FBS against FBS matchups generally require a larger financial guarantee.

The FBS is made up of the larger football programs that have a deeply rooted history in winning on the national stage. These Division 1-A schools are better funded and equipped schools that make up the Division 1 standings. The FCS schools are the smaller Division 1 schools, referred to as Division 1-AA. They are typically smaller schools, with funding that makes it hard to compete with the FBS powerhouses.

“It’s important to note that FBS teams can only count one FCS team each year toward their bowl eligibility win total,” Saal said. “Therefore you typically see FBS teams schedule one FCS and two to three FBS opponents in their non-conference schedule. Similarly, FCS teams will either schedule home-and-home series at no cost to either school or pay to host an FCS or NAIA to complete their non-conference schedules.”

These matchups cost the FCS schools much less than what it would cost a FBS school to host either another FBS school or an FCS school.

The difference in funding and opportunities between the FBS and FCS teams are one of the reasons these profitable “money games” are going to be a standard in college football schedules for the foreseeable future.