If this paper is “hot off the press,” you are reading this essay at the end of what may appropriately be called, “Equality Month.”

It may be so called because two of the world’s greatest advocates of human equality have their birthdays celebrated worldwide in January. They were not politicians nor generals. Neither was ever elected to high public office and both came from professions that were – and are – unlikely to spawn political leaders.

Americans will immediately name Martin Luther King Jr. Before his assassination at the age of 38, he had led a revolution in peaceful protest and led the nation into a new age of political and social equality. A national holiday marks the debt owed by the nation to his wisdom and courage. We celebrate the Monday nearest his birthday Jan. 15.

Most of us, however, would not recognize the contribution of the son of a poor Scottish farmer. Born in the southwest of Scotland, Robert Burns grew to be the best-known poet of his age. Dead for more than two centuries, authorities still recognize him as the greatest poet in the English language. Around the world, his admirers gather for celebratory dinners on his birthday: Jan 25.

Burns led no marches, counseled with no presidents or kings. He headed no movements, nor did he create memorable speeches that stirred a nation to action. In his day, there were no televisions, no elections to compel the powerful to attend the will of the people.

But there were books. Burns’ passionate poems of respect for the common people and his logical appeals for the inherent worth of every individual moved thousands of his fellow Scots. In Scotland, his love of family and country inspired new self-respect among the poor who would soon emigrate to the New World – or be transported against their will by the English king.

Like King, his words proved to be powerful tools to encourage freedom from tyranny and to embolden a belief in self-worth among both men and women.

Although popular with the high-born and the wealthy for the beauty of his verse, he was revered by the common people for the dignity he gave their lives.

You probably sang his great hymn to friendship less than a month ago. “Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind?” we sang on New Year’s Eve. The answer is so obvious, that the poet never provides it. Friendship is forever.

Among his many poems extolling the worth of the individual and casting doubt on the rights of monarchs is the manifesto of equality best known as “A Man’s a man for all that.” After making the powerful argument that a man of character and honesty is of greater value than one who is merely wealthy or high-born, he concludes,

Then let us pray that come it may —

as come it will for all that —

That sense and worth, o’er all the earth

may best be prized, and all that.

For all that, and all that,

It’s coming yet for all that,

That man to man, the world o’er,

Shall brothers be for all that.

One hundred eighty years later, King would call for “the content of their character” to be the standard of acceptance for his children. “Sense and worth” had finally arrived. Burns died of illness in 1796. He was 37.

So, Burns and King are linked by more than a coincidence of birthdays and tragically shortened lives.

They help us all start the year with a reminder of the value of freedom. It’s a great month for equality.

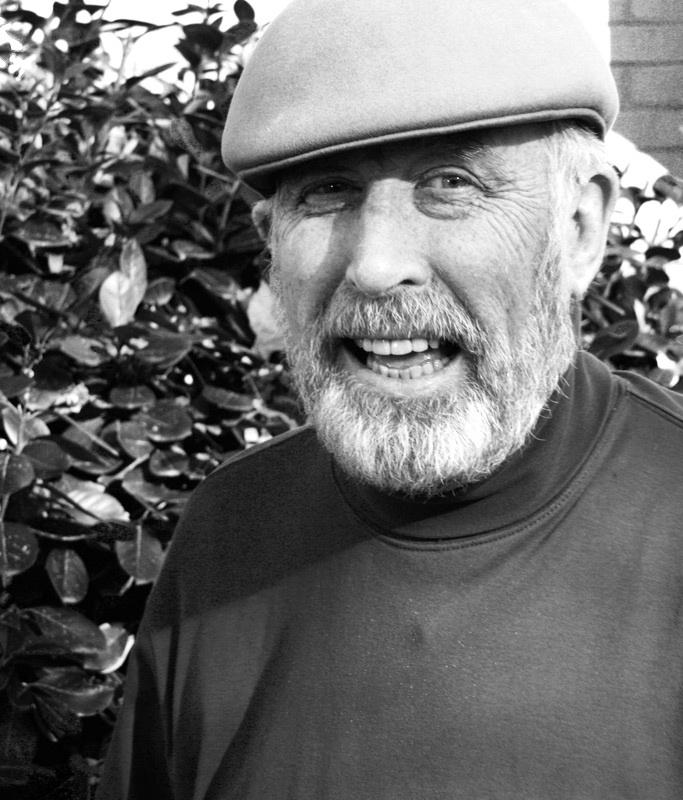

Column by Robert Valentine, Senior lecturer of advertising