How one traumatic night for a student became a six-month struggle with Murray State.

Editor’s Note: The Murray State News changed the name of the woman and decided to not name the alleged perpetrator or any other students involved.

It took Lily Smith two days to fully understand she had been raped.

She said as she stood in the shower thinking about the events of Nov. 7, 2014, she wished the hot water running over her head were acid, eating away flesh and memories.

“If I didn’t ask for this, then what does that make it? The shock of the word ‘rape’ hit me,” Smith said.

It took another three days for her to gather the courage to come forward about what happened.

A saga of unreturned phone calls and email chains ensued, during which she learned the Murray State administrator assigned to guide her through the judicial process is the adviser to the accused rapist’s fraternity.

Colby Bruno, a case advocate with Victim Rights, said that’s a conflict of interest.

“This is just an objectively wrong thing to do,” Bruno said. “He oversees the process. He can make it more or less difficult or spend time not getting back to her.”

Victim Rights, an advocate group based in Boston, Mass., and Portland, Ore., provides free legal aid for sexual assault victims. However, the group was not involved in this case.After 51 emails spanning six months, Smith got a judicial hearing, scheduled to take place behind closed doors April 20.

The man accused by Smith declined to be interviewed.

FIRST STEP

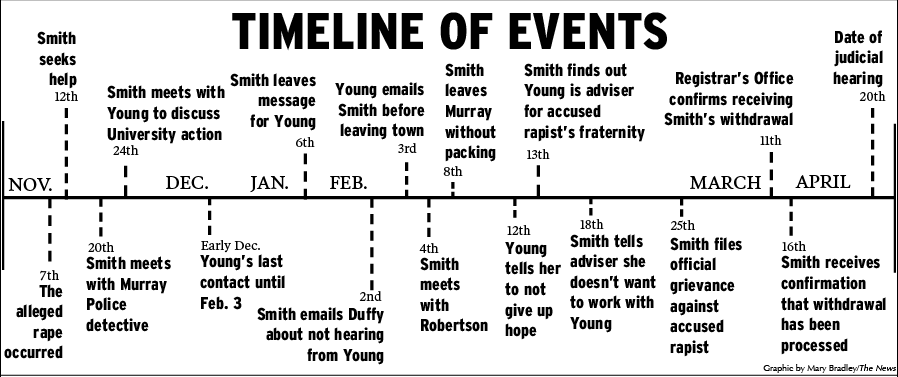

On Nov. 12, Smith decided she needed to speak with authorities about the alleged rape.

But when she went to the Women’s Center, ready to recount the events of Nov. 7, she was greeted by a student worker and a clipboard of paperwork.

Smith said she wasn’t mentally stable. She couldn’t fill out the paperwork.

Smith was told Abigail French, Women’s Center director and a counselor trained to take on sexual assault cases, was the only person who could see her, but was unavailable at the time.

Smith moved to the Counseling Center, where she was told her case would be put in a file to be discussed at the weekly meeting. Someone would be in touch the following week.

A delay was the last thing she said she wanted.

“I’m in the trenches,” Smith said. Having to “hang tight for a week” was a big ask, she said.

In the mean time, she was directed to the Title IX office.

The office, though, is not easy to find in Wells Hall. The Title IX office also is known as the Office of Equal Opportunity (its name on the Wells Hall directory marquee) and as the IDEA office, which stands for Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

A student must follow signs to the IDEA office through the subterranean first floor of Wells Hall.

It’s hidden for a reason, said Camisha Duffy, Murray State’s Title IX coordinator.

“People are coming forward and we don’t want the office to be a public place,” Duffy said.

Once she found the office, Smith retold her story to three University officials: Duffy, Mike Young, interim associate vice president of Student Affairs, and Duffy’s secretary.

Murray State’s process for handling sexual assault complaints divides cases between Duffy and Young. Employee-to-student sexual assaults are handled by Duffy, and student-to-student cases are handled by Young.

Students who come forward about a sexual assault can first report it to different authorities, such as a residential adviser or the police.

But that point of contact often serves only as an entry way to Murray State’s judicial process, as Smith found out.

After a debriefing with Duffy and Young, Smith was given the option to move forward with criminal charges.

Smith decided to talk to the police. Because the assault took place off campus the case fell under the jurisdiction of the Murray Police Department.

The tall, male officer entered the Title IX office in uniform. Smith was left alone with him to tell the events of Nov. 7 again.

“It’s not a policeman’s job to be sympathetic, and I get that,” she said. “But I felt defensive, like I’m pleading my case. It sucks to defend yourself against something that happened to you.”

DEFINING RAPE

For Smith, Nov. 7 began with an invitation from a close female friend to relax and have a drink together. It ended with three strangers added to the group at her friend’s house and Smith drinking more than she had planned. At one point, the four others left Smith alone in the living room, in a drunken sleep on the couch – until one man rejoined her.

At that point, the man raped her, she said.

When she described this to the officer, phrasing Smith used for her state of consciousness came under scrutiny. “Passed-out” implied being totally unconscious, she said the officer told her. She was drunk, she told him. She had fallen into a deep sleep because of the alcohol. He asked if she “blacked out” that night.

No, she told him.

That creates a gray area, she said he told her.

After taking her statement, the officer told Smith he’d hand it over to Angel Clere, the detective assigned to sexual assault cases. She will look it over and be in touch, he told Smith.

Clere was unavailable for comment, but spokesman Sgt. David Howe said the detective would typically go over the statutes defining sexual assault with the victim.

On Nov. 20, Clere told Smith she had met with the alleged perpetrator and took his statement, as well as the statements of three others at the house that night.

There were benchmarks that had to be met with each case, Smith said Clere told her.

“You either have to be completely sober or blacked out,” Smith said. “Those were the benchmarks.”

Because it would be difficult to bring criminal charges, Smith looked for other options.

Murray State’s Title IX program, and many other universities’ Title IX programs in the nation, allow a victim to take the alleged perpetrator to a judicial hearing.

Murray State’s judicial board is made of a mix of students and faculty members, selected for rotating terms. Judges can recuse themselves from proceedings if they believe there is a conflict of interest with a case.

Both parties are given the opportunity to tell their side of the story in a hearing. The panel of judges bases a decision of guilt or innocence on which story is more likely to have happened. Both parties are allowed to bring character witnesses as well as a personal advocate who is restricted to speaking only with their client.

Because Smith’s case involves two students, Young took control.

As part of the Student Affairs staff, Young also was in charge of talking to Smith’s professors about the remaining few weeks of the fall semester.

LEAVING MURRAY

Smith said she said she had to get out of Murray. She stopped attending classes after Nov. 12.

“It had taken over my life,” she said. “My mind wasn’t there. As a student I felt so guilty. I was so close to graduating summa cum laude. I’d been working my butt off all semester. I was a good student and then I was just gone.”

Young and Smith spoke with Smith’s professors and figured out a separate path for finishing the semester. Some classes she left with the grade she had on Nov. 12. Others she finished online.

Smith met with Young Nov. 24 to take formal University action against the man she accused of rape.

In the meeting, Young divulged to Smith that he knew the man, and he was angry with the student. But he did not tell Smith how he knew him. Young told The News he does not remember making the statement.

“I say to everyone that I’m empathetic that you’re going through this,” he said. “If I said anything, it would have been in that vein. Not about this person and this situation.”

The timing also complicated the process. Thanksgiving was three days away and the semester would end two weeks later. Young said he couldn’t speak with the man accused of the rape until after Thanksgiving, giving little time for a judicial hearing to take place before the end of the semester.

Young told The News he spoke with the alleged perpetrator after Thanksgiving Break.

Smith said she heard from Young only once between the end of the fall semester and Feb. 3. It was a phone call from Young in early December, checking on her wellbeing.

Young said he didn’t believe he was difficult to reach. He said he might have emailed with her during that time and would provide The News with copies of the messages. He never did.

After meeting with a therapist over Winter Break, Smith decided to return to Murray State for the spring semester to finish her degree.

“I was afraid there were no other options,” she said. “I just had to grit my teeth and get through it.”

When she reached out to Young Jan. 6, she left a message with a student worker and didn’t hear back.

Still tormented by panic attacks, paranoia and anxiety, by early February Smith knew she couldn’t stay at Murray State. Having still not heard from Young, Smith sent an email to Duffy Feb. 2 asking whom she should contact for emotional and administrative support.

When Smith first came to Title IX, Duffy made sure she was taking care of her physical health, Smith said.

Students come to the Title IX office in all physical and emotional states, and Duffy said she frequently takes on the role of caretaker.

Nov. 14, Smith’s friend told the alleged perpetrator, along with the two others involved, that Smith was thinking about filing rape charges, Smith said.

She could no longer trust a close friend, Smith said. It triggered a nervous breakdown that left her nearly catatonic. She called Duffy.

Duffy came to Smith’s apartment with a burger, fries and a milkshake from Cookout.

“She told me you have to take care of yourself first,” Smith said. “I hadn’t showered or had food all week.”

After the fall semester ended though, Smith was left without a point of contact.

Ideally, a student’s transition between caretaking Duffy and administrative Young should be seamless, Duffy said.

“We generally don’t just abandon a person,” she said. “As best I know we’re doing a good job. We all try to keep in contact with each other.”

But when Duffy responded to Smith’s email on Feb. 2, she seemed confused about the state of the case and the communications.

“Are you not working with Mike Young at this point?” Duffy wrote Smith. “I was under the impression he was still working with you. Is my impression wrong?”

Feb. 3, Smith received a response from Young at 8:17 a.m. asking her if she could meet with him at 10 a.m.

But after working the shift as an overnight front desk worker, she did not wake up to read Young’s email until 10:33 a.m.

The next day, Smith hit a breaking point.

“I was sick of being in the dark,” Smith said. “I decided that if I hadn’t heard anything by the end of the day I was going to his office.”

She emailed Young, asking if there was anyone else she could meet with.

She decided to go to her academic adviser.

Her adviser told her to talk to Don Robertson, vice president of Student Affairs.

On Feb. 4, Smith sat down with Robertson in his office and told him she was sexually assaulted and she felt she could not stay at Murray State.

Robertson called the Bursar’s office, then Abigail French, director of the Women’s Center.

French told Robertson to call Camisha Duffy.

Duffy, at the moment, was tied up at the campus police station with another sexual assault case.

Duffy left the station and came to Robertson’s office.

She called Young, who was in Florida at the time for a conference.

Via conference call, Young told the three in the room that he was 12 hours away and he couldn’t do much from the conference.

“We do try to minimize the number of folks who are working with that particular individual,” Duffy said.

But by Feb. 4, at least six University faculty members had been brought in on the case, and still no date had been set for the judicial hearing.

“I recognize the fact that you are quite busy and not in Murray, but I need to alert you that I have reached my breaking point here in Murray, and I need to leave,” Smith wrote Young in an email Feb. 4, before going to her adviser. “I thought I could make it through one more semester, but the past three weeks has proven that is not going to happen.”

In the conference call, Young told Smith to email her class schedule and professors’ names to him. He said he would see what her options were.

Four days later, on Feb. 8, Smith left Murray without packing, unable to stand being in the city any longer.

PERCEPTION

At this point, Smith still wanted to finish her classes online from her hometown, and she was still trying to schedule the judicial hearing.

Young tried to reach Smith the morning of Feb. 10. In returning his call, she left two messages for him before they finally connected around 4 p.m. He told her he was contacting her professors.

In a follow-up email Feb. 12, Young told Smith “Don’t give up hope as I am still in conversations with your professors as well as (the) Registrar’s office.”

Two minutes later, Smith replied.

“Thank you for the contact, as hopelessness is the dominant feeling right now,” she wrote.

When she returned to Murray to gather clothes and toiletries Feb. 13, she found out through a friend that Young served as the adviser to the fraternity of which the accused rapist was a member.

“It was enraging and horrifying,” Smith said. “Suddenly it all made sense why it had been taking so long. I was done with Mike Young. I didn’t want to work with him anymore.”

She made the decision to withdraw from Murray State, a process that would take three more weeks.

Young said he didn’t believe his role with the man’s fraternity was necessary to divulge. He said his role in the case was limited to the process of putting the judicial hearing together. He has no input in the proceedings of the hearing itself, eliminating the chance for bias, he said.

To reduce the chance for conflict of interest allegations, Young brought in Jennifer Caldwell, assistant director of Housing, to help set up the hearing.

Young said his role was to provide students information about resources available during the Title IX process.

“I’m doing the process of the hearing, making sure both sides have equal opportunity to the same set of services that we offer as it relates to a conduct hearing,” Young said.

Don Robertson, vice president of Student Affairs and Young’s superior, said Young wouldn’t have participated in the judicial hearings.

“I think the right thing was to say, because there could be a perception at the hearing time, ‘I’m removing myself,’” Robertson said.

He also said he didn’t think Young’s affiliation with the man was a problem because Young’s role is simply explain how the process works, but he conceded that Smith was upset by it.

“But it just has no bearing on what was going on,” he said.

According to Young and Robertson, there was no conflict of interest.

According to Colby Bruno, there was.

Whether Young is unbiased isn’t the issue, Bruno said.

“The question is objectively, could there be conflict of interest?” she said.

She said the potential for a conflict must be disclosed in order for the students involved to elect to have another faculty member guide them.

“At the very least,” Bruno said, “she should have been given the choice.”

Story by Amanda Grau, Staff writer